|

Issue 20 (1/2007)

|

|||

FSD Bulletin is the electronic newsletter of the Finnish Social Science Data Archive. The Bulletin provides information and news related to the data archive and social science research.

|

WVS, Economists and HappinessEsa Mangeloja, Doctor of Science (Economics), Master of Social Sciences, Bachelor of Theology The scientific community is increasingly interested in happiness. In addition to psychologists and social scientists, in recent years also economists have begun to study factors affecting people's happiness (Hirvonen and Mangeloja, 2006). After all, we can say that the pursuit of happiness lies behind all human activities, thus also behind the pursuit of economic well-being. This article explores the question of happiness using World Values Survey data. Finns are happyFor studying happiness, the most relevant question in the 1999-2001 WVS was "Taking all things together, would you say you are", and the answer options were "Very happy, Quite happy, Not very happy, Not at all happy". In the year 2000 data collection, 1035 Finns responded to this question. The data reveal some interesting and surprising facts about reported happiness in Finland. The first unexpected result is that as a whole Finns consider themselves to be surprisingly happy. Nearly one in four respondents reported themselves as very happy whereas only 1,3% were not at all happy. A clear majority, 66%, said that they were quite happy. The results indicate that Finns generally are a happy bunch. This is contradictory to the gloomy picture painted by the media or some social critics as they tend to harp on the anxiety and unhappiness of Finnish citizens. Growing alcohol consumption and the short-term and long-term problems caused by it are taken to be the clearest signs of unhappiness. The data on reported happiness do not confirm this dismal picture (Hirvonen and Mangeloja 2005a).

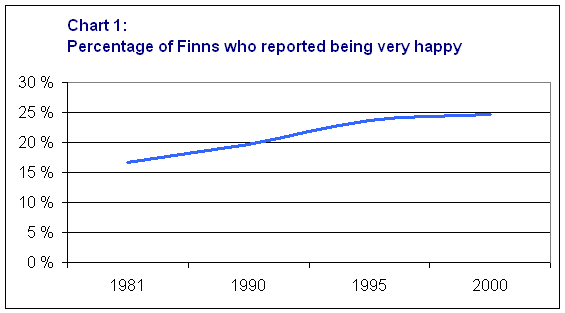

Another interesting and unexpected finding is that there has been little change in the level of Finnish happiness over the decades. In 1981 roughly 93% saw themselves as at least quite happy. In 1990 the percentage was 87% and in 2000 it was 90%. Chart 1 displays the change in the percentage of Finns who reported being Very happy. We can see that their share has grown a bit higher over the years, though not by much. WVS data show that as a rule there has been little change in the share of happy people in Western countries. On one hand this is a consolation: the direction into which modern society has developed has not made us any unhappier. For economists, on the other hand, this is a paradox. The Western world has witnessed an unprecedented growth in material well-being over the past decades. Western people are wealthier than ever before (Hirvonen and Mangeloja 2005b). Ambitious goals set by economists and politicians have been reached. Many economists would have expected people's happiness to grow in the same proportion but this is not what has happened. Higher income does not mean happier people

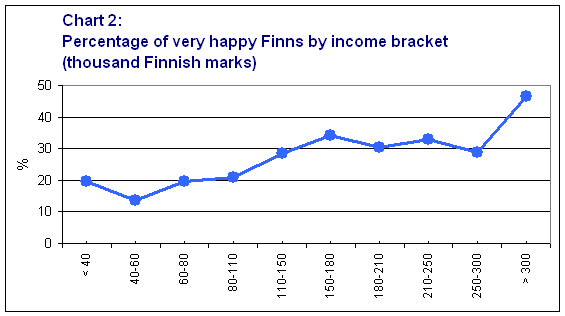

Studying the happiness of Finns, we can see that increase in income increases happiness only slightly. Chart 2 illustrates the percentage of people reporting to be Very happy by income bracket (source: the Finnish data of the 2000 WVS). The higher the income is the bigger the share of happy people. The line is not vertical, however, as the share of happy people declines in the 'slightly wealthier than average' income bracket. Poor persons are less happy than those with higher income. We can conclude that even if income and happiness correlate, it is mainly other factors which influence and shape our happiness. Wealth is linked to several positive factors in life like better state of health, longevity, lower mortality and better educational achievement whereas financial problems are seen as a cause for depression. On the other hand, wealth has its disadvantages. Most people have to earn their wealth which means long working hours. Social relationships suffer and there is little spare time. People get used to wealth quickly, and higher expectations and demands counteract the tendency of income to contribute to happiness gains. Getting richer may also require a materialistic world view and values which in themselves lower reported happiness (Diener and Biswas-Diener 2002). In Western countries the coefficient of correlation between income and happiness usually varies between 0,12 - 0,18. Finland, with its 013, is a typical case. How strong the correlation between income and happiness is depends on the wealth and general well-being in the area. The correlation is higher in poor areas, in Indian villages 0,22 and in the slums of Calcutta 0,45 (Biswas-Diener and Diener 2001). Understandably, the correlation is higher in poor areas, where poverty signifies lack of basic necessities of life (food and shelter), than in the affluent West. Similarly, income loses its importance in higher income brackets. To use the terminology of economics, income has diminishing marginal utility. The effect of increased income on happiness becomes progressively smaller the higher a person's income is. Researchers have taken into account other variables which may have an impact on happiness: the level of education (small impact), marriage (fairly big impact) and employment (big negative impact, especially for men). The results indicate gender differences: the correlation between income and happiness is stronger for men. Low income raises depression risk in single women but not in married women (Keith and Schafer 1982). Poverty increases depression risk but marriage reduces it. The correlation between income and happiness grows smaller with age. There are reasons to assume that the impact of income on happiness largely depends on a person's life situation, and role in the community. The correlation is not stable but varies in time, from society to society and between individuals. WVS makes researchers happySocial scientists and economists can use the WVS data to broaden their ideas on people's well-being. Cross-national surveys help to investigate factors influencing people's lives and well-being on a broader scale that can be achieved by studying economic factors only. A variety of factors, most of them non-economic, have an impact on the level of happiness. WVS offers the possibility to study a number of variables, and allows cross-national comparisons and analyses over time. The survey series offers plenty of material both for social scientist and economists. More information on WVSReferences

Diener, Ed and Biswas-Diener, Robert (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? A literature review and guide to needed research. Social Indicators Research, 57, 119-169. |